#35 – Ditches and Stitches: Technically Speaking

In our most recent posts, we have been looking at how the

Drum Family Tree members spent their days. We began with how they spent their

free time, you know, the books that they read, then the newspaper clippings

that they clipped out of their newspapers. We also looked at one of these

articles in a rather “in-depth” way.

Now we turn to how they got through their day to get to

the free time. Sometimes they needed information to help them get through the

day and books and newspapers weren’t enough. They needed information sources

that didn’t just tell them stories ABOUT what happened, they needed to know how

to MAKE stuff happen; how to DO stuff!

What they needed were some good Almanacs and Technical

Guides.

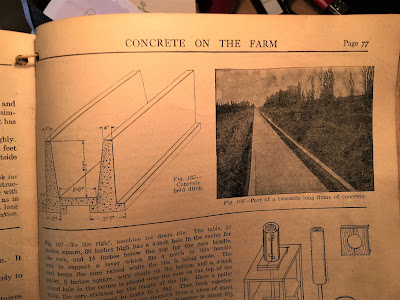

Page 76 of Concrete on the Farm begins:

The economy of farm drainage is well known. Wet lands

are not only unsightly but unprofitable…. The simplest remedy is a drainage

ditch. The best possible material for the drainage ditch is concrete…

It goes on to tell how to use this concrete to solve the

problem.

On Page 77 they show a picture of what they are talking

about.

However, what if you wanted a round tank instead of a long trench?

Page 9. To calculate for anything circular there is

one rule to remember: the area of a circle is found by multiplying the diameter

by the diameter, then multiplying the result by 3 1/7 and dividing by 4.

Well, who doesn’t know that!? Like we had to be told, or

something.

|

| This is the back of the guide showing the logo and who handed it out. Since it is the back, the hole and string are in the upper right corner of this photo. |

Concrete on the

Farm is a handy “how

to” guide that was published in 1919 by The Atlas Portland Cement Company. As

we can see from the back cover, it apparently was distributed in the Hazleton

Area by Jere. Woodward & Co. of Hazleton, PA. Up in the upper left-hand

corner (upper right, in this photo since this is a photo of the back, not the

front, of the booklet) is a drilled hole and laced through that hole is a loop

of string making it handy to hang up in the barn or work shed for easy

reference.

I don’t know if the Atlas Portland Cement Company did

that or if Elmer Drum did it. Most likely, the company drilled the hole and

Elmer laced the string. I guess it would be a handy guide to have hanging

around, if you did a lot of cement work on your farm. It tells you stuff like

the correct mixture of “aggregate” and cement for your various projects; how to

pour a concrete floor; the advantages of a circular concrete tank over a square

one; types of, and how to construct, concrete sidewalks; not to mention how to calculate

for anything circular and how to make a concrete ditch. You name it, they

“cover” it; they just “pour out” the hard facts, you might say.

By the way, they do define “aggregate” (even show

pictures!)

They also provide information on the various forms of cement

that exist, including “Portland”. They don’t forget telling a bit about its

history, either. Of course, they further suggest that Atlas Portland

Cement is the best brand of the Portland Cements to be had. After all, it’s “The

Standard by which all other makes are measured”!

If you haven’t figured it out yet, this post is about the

HARD facts of life! In the following photo we see more of those hard facts, or,

rather, the guides they are in. You would have found these publications on most

farms in earlier years. Right off we see our friend, Concrete on the Farm

(this time from the front). Clockwise to its right is a guide from 1904

entitled The Business Hen. No, this is not a book about a chicken

running a business. This title means, if you are going to go to all the trouble

of raising chickens, you might as well make it a business and get some money out

of those chickens! Below the “Hen” is an agricultural almanac from 1925.

Sitting at “6 o’clock” is another agricultural almanac, this one from 1923.

Finally, on the left side of the picture is a third agricultural almanac, this

one from 1953.

It took me a while (too long, actually) to realize the

significance of these almanacs. The year 1923 was the year my father was born.

His sister, my Aunt Clara, was born in 1925. Either Elmer or Ella or both preserved

these two almanacs probably because they were from the years their children

were born. I’m sorry to say that if the same theory applies to the third

almanac, from 1953, in the collection, I’m not yet quite settled on what the

connection may be. Perhaps there isn’t any. However, 1953 is the year my dad

began building Drumyngham. Perhaps that was significance enough, but I probably

would have kept the one from the year the house was COMPLETED.

Almanacs did play a role in the everyday life of the farmer.

Today we have sophisticated weather prediction services and state university

Cooperative Extension agricultural specialists we rely upon to help us

determine proper planting times (after last frost), growing season length

(quantity of rain), harvest times, methods (contour plowing, tilling, etc), and

so forth. Farmers of earlier times got their information from the almanac.

For those who believe in the zodiac and horoscopes, the

almanac will help you know what constellations are in force at given times (for

example there is a rule that says you should not make sauerkraut at the time of

Aquarius). From the 1923 almanac we learn that a total eclipse of the sun was

going to occur on September 10, however, it would only be seen as a partial

eclipse in the United States. The 1925 almanac suggests that rubbing thread

with dry soap will make stitching through heavy cotton easier. The 1953 almanac

say that the louder the katy-dids and crickets call in August, the bigger the

blizzards will be in December. It says this was born out in 1951, so be

forewarned!

Quiet Augusts, that’s what we want. Quiet Augusts.

These almanacs were also a source of entertainment. Both

the 1923 and the 1925 almanacs relate humorous stories that I refuse to retell

because they are racist (which suggests how times have changed). However, here

is one from the 1953 almanac we can chuckle about. It is a story about a farmer

whose farm was so close to the Pennsylvania/New York border, he wasn’t sure

which state his farm was actually in. So, he invited officials from both states

to do surveys and finally settle the matter. After much consideration they

finally determined his farm was in Pennsylvania. “Good, he replied. “I never

could stand those tough New York winters!”

I believe the earliest of these guides and almanacs that

are in the collection is George Drum’s 1885 The Handy

Housekeeper.[1] It

appears to be a collection of articles that appeared in a magazine called Our

Country Cousin, one of the publications produced by Wilmer Atkinson, publisher/founder of the Farm Journal.

This photo of Atkinson was another one of the many

clippings found in the "Hat Box" Collection, probably added by Jacob Santee. This

collection has been noted in a number of previous posts, most recently in Extra!

Extra! Read all about it!

This photo of Atkinson was another one of the many

clippings found in the "Hat Box" Collection, probably added by Jacob Santee. This

collection has been noted in a number of previous posts, most recently in Extra!

Extra! Read all about it!

This little book covers quite a bit of information useful

to someone running a household on a farm. The table of contents starts with

“Antidotes for Poison” and ends with “Wash Day”. “Dairy Work”, “Good Manners”,

“Health Tips” and “School Lunches” are among the many topics in-between.

There’s even one chapter entitled “Taking Care of Things”! I’ll have to read

that one.

The front cover is missing. On what appears to be the

inside front-cover page, lightly written in pencil, up against the right edge of the page, appears the following:

1886

Geo Drum

Drums

Luzerne

County

PA

That’s how we know it belonged to George Drum. The

question is, however, which George Drum? By my estimation, we have three

candidates. Abraham’s son, George (born 1827. Died 1890); George Jr’s son

George W. (born 1832. Died 1913); and John’s son George B. McC. (born 1865.

Died 1931).

My guess is that it was John’s son, George B. McC., who

was the George who once owned this book. Abraham’s son was involved with the

Stagecoach Stop out at Sand Spring (on the present Route 309) and George W. was

living in Conyngham. John’s son was the proprietor of the Drums Hotel by 1886,

John having died in 1881. John’s George was living closer to Nathan and Elmer -

all living in Fritzingertown - than the other two Georges, so it makes sense

that we might have John’s son’s papers (at least this book) in our collection.

Just two more almanacs to look at, Lum and Abner’s

Adventures in Hollywood and 1938 Family Almanac and The Farmer’s Almanac

2000. That second one was obviously added to the collection by me. Had I

been as smart as my Grandfather, I’d have saved the almanac for 1995, the year

my son was born. This one is second best, however. It’s the almanac for the

last year of the 20th Century. Seemed worth keeping.

Lum and Abner’s is a different thing again. I wasn’t sure

what this was at first. However, paging through it, it appears to be an almanac

just as any other almanac might be. It just uses the theme of Lum and Abner, a

popular radio show from the 1930’s into the 1950’s, to put the information and it’s

stories (the entertainment aspect) across. I’m guessing Elmer, Ella and the two

children would gather around the radio in the evenings to listen to, and laugh

over, the antics of Lum and Abner.

In addition to almanacs, technical information was gotten

from journals and a few newspapers as well. In the next photo we see some of

these that were saved. Most of these were marked with the reason it was saved.

Number 1 is the December 19, 1888 edition of The

Weekly Sun. This one was a “two-for”! Across the top is written “to keep

cider sweet” and “cholera cure”. Those seem like good reasons to keep

something.

Number 2 was saved on March 25, 1893. This edition of Rural New Yorker was saved because it had

information on how “to reclaim waste land” on page 205.

Number 3 is the oldest of this group. Called the American

Agriculturist, published in December 1874, the info it was saved for was

about concrete walls with the note “a neat little trick” added as well.

Number 4 is the November 25, 1890 edition of The Word.

Across the top, in pencil, is written “Making hens lay in winter” which,

frankly, sounds sort of mean. Just saying.

Number 5 is the youngest of this group. It is the October

16, 1926 edition of the Rural New Yorker saved for the information it

includes on “Grape Juice to make”.

Number 6 is a Rural New Yorker from May 7, 1892.

It is marked “Bring youth to an old meadow” which, I thought, until I read it,

was about establishing a youth camp. (kidding)

Number 7 - “Elderberry Wine” was the reason this July 20,

1901 edition of the American Agriculturist was saved. Even though they

didn’t know it at the time, that one probably turned out to be a great “keeper”

given what happened in 1920 (Prohibition).

At first glance, the book The Complete Home Handyman’s Guide[2], shown in the next photo, would seem

to be offering the same information as George Drum’s edition of The Handy

Housekeeper. But no, it does not. The “Home Handyman’s Guide”

offers, according to the cover page, “Helpful suggestions for making repairs

and improvements in and around the house”. Handy Housekeeper is talking about

housekeeping, not house repairing. So instead of pickles, poison, and wash day

hints, Home Handyman is covering topics such as plumbing, heating,

working with metal, and handyman hints. It was published in 1948.

The booklet in the photo with the Handyman’s Guide is

everything you’d ever want to know about Solder. At least, it’s everything I’d

ever want to know about it, anyway; actually, MORE than I’d ever want to know!

Soldering is what you do when you want to connect two wires together. I’m sure

this was one of my dad’s resources. It was published in 1961.

I, too, made contributions to the “Do It Yourself”

Technical guides in the collection. In 1971, I added The Pleasures of Cigar

Smoking. I found it to be an interesting read. After all, you don’t want to

be seen as someone just blowing smoke, do you?

I, too, made contributions to the “Do It Yourself”

Technical guides in the collection. In 1971, I added The Pleasures of Cigar

Smoking. I found it to be an interesting read. After all, you don’t want to

be seen as someone just blowing smoke, do you?

Ok, I apologize for that, but I did, at least, WRITE one!

Air Force and 4-H: Working Together for the Future,

written in 2002, explains how 4‑H programs can be established on Air Force

installations through a collaborative effort between youth serving Air Force

agencies and the county 4-H office. I discuss this program a tad more in an

earlier post entitled Some

of us Never Went to War.

Air Force and 4-H: Working Together for the Future,

written in 2002, explains how 4‑H programs can be established on Air Force

installations through a collaborative effort between youth serving Air Force

agencies and the county 4-H office. I discuss this program a tad more in an

earlier post entitled Some

of us Never Went to War. However, getting back to the contributions of “the tree”,

here is another of my dad’s guides. This one is about Jig Saws and Band Saws.

It was published by Sears, Roebuck and Co. in 1950. That was a good year! The

year 1950 was also the year Mom and Dad were married. That fact probably has

nothing to do with the booklet on saws, but it certainly has something to do

with the next picture.

However, getting back to the contributions of “the tree”,

here is another of my dad’s guides. This one is about Jig Saws and Band Saws.

It was published by Sears, Roebuck and Co. in 1950. That was a good year! The

year 1950 was also the year Mom and Dad were married. That fact probably has

nothing to do with the booklet on saws, but it certainly has something to do

with the next picture.  This is my mom’s sewing bucket. It was much better

organized when she was working with it. The bucket was purchased by my dad for

my mom while they were traveling through New England on their Honeymoon.

This is my mom’s sewing bucket. It was much better

organized when she was working with it. The bucket was purchased by my dad for

my mom while they were traveling through New England on their Honeymoon.

By the way, in case you are wondering, that egg-shaped thing

in the bucket is a “sock egg”, at least that’s what Mom called it. Apparently,

if you have a hole in your sock, pushing this thing into the sock makes mending

the hole easier. At least that’s what Mom said.

Why am I showing Mom’s sewing bucket? So far, we’ve been

focused on guides that are highly relevant to farming or technical skills such

as carpentry or pouring concrete. I thought, therefore, that I’d change the

subject to show that skills such as sewing and cooking were also covered. So, I

used my mom’s sewing bucket to do that. In an earlier time, we might have just

said, “And now something for the Ladies!” However, we are living in a more

enlightened time now. Men sew and cook too, you know.

I know I do! I admit I could do a better job at cleaning

the house, however. Say, I wonder if George’s booklet might offer some

suggestions…

So, what is the ultimate “do it yourself” book? Why the

COOKBOOK of COURSE!

Truth be told, the top two booklets in the above photo are

the only two included in this photo that were “Drum Tree” contributions: The

Enterprising Housekeeper (1900) and The Cookie Book (1941).

Most of the

“cookbooks” I’ve seen saved by this family seem to be collections of recipes that

were hand-written on single sheets of paper or were on pages torn from

newspapers/magazines, sometimes glued onto notebook paper, and saved in an

envelope or folder. For example, here is one from my Grandmother’s (Bertha Shearer) collection

that my mom glued into a notebook. In her note below the recipe she points out

that it is “written in Mom’s handwrtting.”

The rest of the booklets in the collection-of-cookbooks photo above came into the

collection via my wife’s “tree”. First up of those is a book that really knows

its (corn) starch, Delightful Cooking (1925). The pink one is Sour

Cream: The Gourmet Touch to Everyday Cooking, produced by the American

Dairy Association about 1950. The Betty Crocker Bisquick Cook Book is

seen next (1956). On the bottom row we see Meat Recipes: 103 Prize winning

recipes with the compliments of the National Live Stock and Meat Board. It

was distributed by the Eastern

States Exposition in 1926. Next to that is What’s New in Cookery

from the Mirro

Test Kitchen. That is also from 1926. Last, we find a 1905 edition of Hood’s Pickles and

Preserves etcetera.

That’s not to say that there were no cook BOOKS in the

Drum collection, just that only the ones of a more recent publication year

survived. Here are two examples. The Good Housekeeping Cook Book of 1941

(with notes written by my mom on numerous pages throughout thrown in at no extra

charge) and A Taste of the Valley, a

compilation of church members’ favorite recipes published by St. John Don Bosco

Church, Conyngham, PA in 1989.

A Taste of the Valley was produced by a church

committee of 13 members. One of those members was Dorothy Staudenmeier. Dorothy

was a very close friend of my mom’s and this was obviously a gift. On the

inside cover page Dorothy wrote, “Dear Eleanor, Enjoy the cookbook and know

we have hope your recipes for health and happiness are many. Sincerely, Dorothy

Our last “guide” comes to us again from the "Hat Box" collection. I know that I am showing it with a sewing machine from 1950 but it

is really all about hand-stitching. It was published in April, 1913. This

article from The Farmer’s Wife shows the reader how to make a “Blanket

Stitch or Flat Buttonhole Stitch”, the “Chain” stitch, a “Herringbone or Catch”

stitch, the “French Knot” (not to be confused with the “Ron’s Knot” which is

what I end up with when I try to sew), the “Cross” stitch, the “Outline or

Stem” stitch, and the “Satin” stitch. If

you really know your stitches, you can pick out the ones I mentioned from the

diagram seen in the picture that follows.

I guess that runs this thread out about as far as it will

go. Join us again on December 10, 2019 when we will be looking at more of the

ways our ancestors occupied their time, that is, their occupations, in Somebody’s

got to do it! (The jobs we did.).